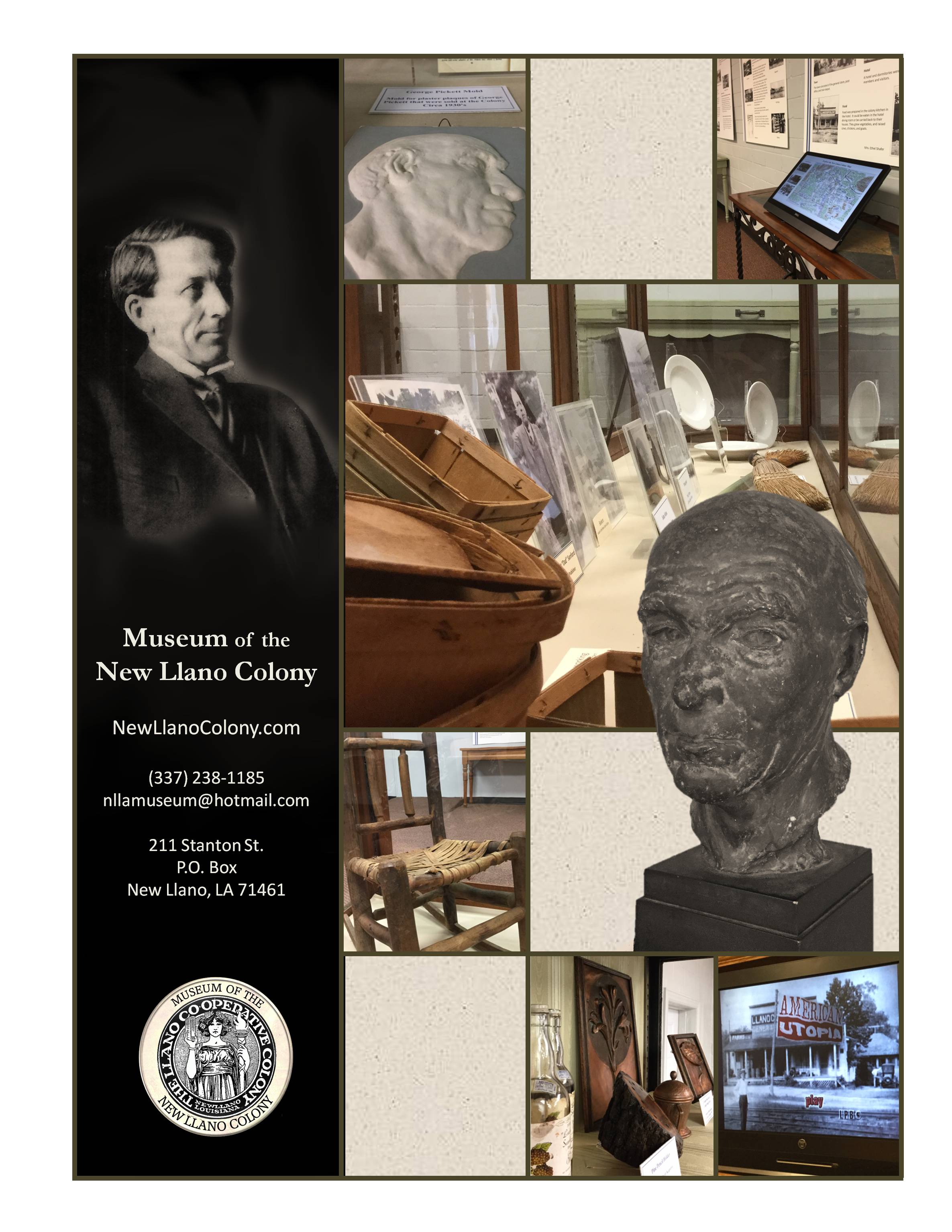

Museum of the New Llano Colony

The Llano Colony as I See It

Episode 3: What the Colonists Found When they Arrived in Louisiana --- 2/3/2017

Celebrating the Colony's Move to Louisiana 100 Years Ago

As we saw in the previous podcast, the reasons for leaving the first location in the Antelope Valley were gradually accumulating. As Dr. Robert K. Williams said, "We must find a new home. Here we have learned that nature, while beautiful, is not kind".

In late 1917, a man named James D. Scoggins, from Texas, visited the colony and told them about a tract of 20,000 acres of cut-over pine lands in Louisiana. He also promised to get a group of people from Texas whose membership fees would provide thousands of dollars to finance the new location.

After some investigation was done on the property the plan was accepted by the colonists and preparations for the move were soon underway. 7,000 rabbits were canned to be used for provisions during the journey and for the coming winter.

On November 17, 1917, four cars left Llano together on a trip that took twenty-three days. In a story that "Doc" Williams wrote for the Western Comrade, he admitted that there were times on the trip when he "hated the whole wad of them" (referring to his passengers) and they, all of them, at times "talked to him in a most heinous fashion." For the trip they took along a variety of essential tools, including guns, cooking utensils, tools and bedding.

Soon after, another group departed, carrying the printing plant and wood-working machinery. The main body of 132 persons traveled on a chartered train of twelve cars which also brought their household goods and other industrial equipment.

The property they found on arrival was almost entirely covered in stumps. Scattered old growths of hardwood, along with smaller sections of pines would serve to supply the colony with all of its lumber needs for many years to come.

The town itself sat on a hill in the middle of one of the hardwood groves and houses were scattered about, some of them in a better state of repair than others. Since the plan was to build new homes as quickly as possible, little effort would be made to do more than the most pressing repairs, though as it turned out, there would always be a housing shortage in the colony, so few of these homes were ever removed -- and though some new homes were built, the primary focus was always to build more and better industries.

The list of buildings they found on arrival included 27 good habitable houses along with 100 cheap houses; an 18-room hotel in fairly good condition; a store, office and concrete power house; three very large sheds and eight smaller ones; 5 concrete drying kilns and an abandoned railroad bed with ties -- but no rails -- which ran through the middle of the tract. Most of these sheds and the railroad bed would eventually be dismantled and the materials used to build new structures.

The pioneers quickly set about the business of making the town their home. It wouldn't prove to be an easy task, however.

Serious problems soon arose when the Texans who had been convinced to join the colony in their Louisiana venture, discovered that they'd been mislead since they wanted no part of a co-operative colony . Apparently, Mr. Scoggins had not fully explained the lifestyle and now they refused to stay -- even worse, they wanted all their livestock and farming equipment back -- things which the colonists had depended on to get them started. They even demanded to be paid for the use of their stock and farm equipment which had been used by all during the time they were at the colony. Eventually, after many threats and several physical altercations, their possessions were returned and they grudgingly departed. Without livestock to pull the plows, men from the colony were forced into the harness and pulled the plows themselves.

About the same time, Harriman received an urgent call from California. Gentry McCorkle, the banker who'd helped Harriman finance the original colony and who was still serving on the Board of Directors as secretary of the corporation, had generously offered loans to colony officials there, but McCorkle soon did a turn-about and began foreclosure proceedings against the colony in an attempt to gain possession of the property for himself.

Harriman returned immediately to California and explained to McCorkle that his transactions were the transactions of a trustee, and that whatever he had acquired in his name could only be held by him as a trustee of the colony since he'd been an officer of the board when the same was acquired. His attorney evidently accepted this theory and a compromise was made, although the property in California was lost. They agreed to put the property up for sale, pay the debts with the proceeds and divide the remainder.

The case lasted several months and Harriman, who had suffered from tuberculosis since childhood, was so weakened by the ordeal that he was unable to return to the humid Louisiana environment. He traveled to Brazil for medical treatment and though he didn't know it at the time, he would not return to the colony until January, 1923. His good friend and vice-president of the colony, Ernest Wooster, was left in charge while he was away.

Other, more immediate problems soon confronted the colonists, however, when they faced a severe drought in the first year and so much rain that their seeds rotted in the ground during the second. There were many debts and the neighbors weren't especially friendly. Many gave up the experiment and left. In 1918 there were only 65 members remaining.

Beginning in 1919, when Wooster was almost ready to throw in the towel, colonist George Pickett was sent out to solicit for new members. He proved to be good at this and in 1920 was elected to be the General Manager of the colony. Though Harriman remained President of the colony, Pickett ran the day to day operations from this point on.

But the shoe shop was making a small profit and slowly a wood business was being built up which supplied firewood harvested from the old lumber at the colony to markets in Beaumont, Texas. In addition, spirits were lifted when re-enforcements arrived in August -- Ole Synoground came with his family and was soon followed by W.A. and Martha Dougherty with their son John.

With grim determination the colonists struggled through these first difficult years. They had established several industries, among which were the store with the butcher shop and bakery; the print shop putting out two newspapers each week, the shoe repair shop; the peanut butter factory; the tailor shop; the machine shop and lumberyard; several poultry yards and a sweet potato dryer. Despite the difficulties, the foundations of the future colony had been laid.

The Museum of the New Llano Colony is open Tuesday through Friday from 10am to 4pm. We'd love to have you stop by and hear more about this unique bit of Louisiana history.

Sources:

Llano Colonist - The Story of Llano: February 25 , 1933; March 4, 1933; March 11, 1933

Western Comrade: October 1917; December-January 1917-1918; February, 1918

Copyright 2018 Museum of the New Llano Colony